Learning Disability

and ADHD Support

When You Need It.

Resources For

Greater Success

We hope that this website supports your journey as you navigate the struggles related to LD and ADHD and build upon your strengths, in order to reach your full potential. Know that you are not alone, and we are here to help you along the way.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Have a Question? Get in Touch Today!

Latest News

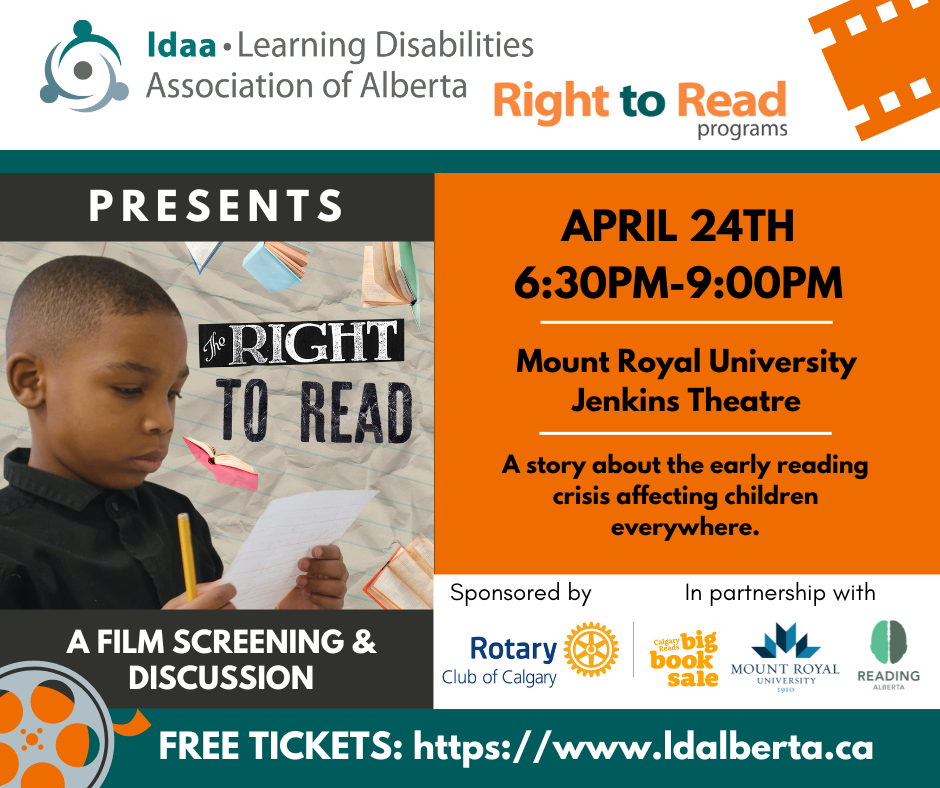

Rigth To Read Film Screening

The Right To Read documentary is a must see to understand the state of literacy today and the science to move it ahead.

Click Read More for free tickets.

April 2024 Newsletter

Latest News | Families & Adults | Educators & Employers | And More!

March 2024 Newsletter

Latest News | Families & Adults | Educators & Employers | And More!

Join us at an Upcoming Event

Edmonton, Alberta

EXPERT: Peg Dawson, Ed.D., NCSP This all-day session is part of the Edmonton Educators Workshop Series May 6 - 8, 2024. Attend in person or live stream. Executive function is a […]

Edmonton, Alberta

EXPERT: Caroline Buzanko, Ph.D., R. Psych This all-day session is part of the Edmonton Educators Workshop Seriesp Series May 6 - 8, 2024. Attend in person or live stream. In today’s […]

How Cannabis Use Affects ADHD Symptoms and Sleep in Adolescents EXPERT: Mariely Hernandez, Ph.D. The increasing decriminalization of cannabis and cannabis-derived products has resulted in greater access to the drug […]

Recent Informational Articles

Learn more about LDs and ADHD, and find helpful information and insights on the assessment, diagnosis and management of these learning and attention challenges.

Self-advocacy is a term that is used quite often within the context of learning disabilities and ADHD. Generally speaking, self-advocacy refers to the ability to know what you may need in a particular situation and the ability to ask for what you need in that moment. With both learning disabilities and ADHD, knowing what you need may not always be obvious and knowing how to ask may be easier said than done. As an educational psychologist, part of my job is to help clients become more skilled and confident with knowing when and how to ask for what they need. An important aspect of self-advocacy is developing insight into your own strengths and challenges, which can be learned through the psychoeducational assessment process.

How Assessments Help with Self-Advocacy

Psychoeducational assessments can serve a variety of purposes. They can provide a profile of the individual’s learning strengths and challenges, identify any learning disabilities or other barriers to learning, and clarify what strategies or programming the individual may benefit from. As an educational psychologist, I have observed how the knowledge that is gained from a psychoeducational assessment can empower my clients to advocate for themselves at school, work, in the community and in their personal relationships.

An assessment provides a diagnosis or explanation as to why an individual struggles with learning or managing aspects of their life, which can empower the individual to ask for what they need to be successful. However, it is important to note that self-advocacy not only requires knowing your diagnosis, but it is also important to have a firm understanding of how your diagnosis impacts you in daily life. For example, ADHD can cause stress for some people in social settings if they struggle with impulsivity (e.g., interrupting during conversations). When I deliver assessment results to my clients, I also provide information about the diagnosis, how we currently understand it through research, and generally what types of strategies and supports have helped others with the same diagnosis.

When you receive any diagnosis from any medical practitioner, you should be allowed to ask questions about the diagnosis, how it impacts you now, how it may impact you in the future, and what resources and supports are available to you. Sometimes, there is not enough time at one appointment to discuss assessment results and next steps for supporting you or your child, so ask the practitioner if you can meet with them again in the near future with any additional questions you may have.

Disclosing the Diagnosis and Asking for Supports

Another important topic that I discuss with my clients after providing them with assessment results is issues related to disclosing the diagnosis to others. Learning how and when to disclose your diagnosis is an important part of self-advocacy. It allows you to take control of your personal information and how it will be used to access supports and accommodations at school and work.

Because each client has their own unique background, I discuss the pros and cons of disclosing their diagnosis in various settings specific to them, such as school versus work versus with family members. When you complete an assessment with your practitioner be sure to have a discussion with them about disclosing your diagnosis to others and how that may impact you. For example, ask your practitioner how disclosing your diagnosis at work may be beneficial for receiving certain accommodations (e.g., speech-to-text programs). Being thoughtful about how and when you disclose your diagnosis is critical for self-advocacy.

Having Realistic Expectations for Self-Advocacy

When I work with families, I often discuss the importance of parents helping their children to develop self-advocacy skills as they mature. However, I also point out that self-advocacy is not easy for most of us, and it can be even more difficult for youth who have difficulties with executive functioning. Learning disabilities and ADHD often involve challenges with self-monitoring, planning and thinking about future outcomes. It is important that parents also understand that their child may not always know when they need to advocate for themselves or how to do so.

Having a balanced approach with youth who are still developing their executive functioning skills is important. Parents and teachers can help youth to gain confidence to ask for what they need, but also provide support and guidance at times when youth struggle to know what they need and how to ask for it. For example, a parent or teacher may notice that a student is struggling to stay focused on their schoolwork. They could ask the student, “I’ve noticed that you might be having some difficulty staying focused right now, what do you think would be helpful for you?” and in this way, help to remind them of existing strategies they can choose from. This balanced approach becomes particularly important in high school as academic demands increase along with expectations for increased independence.

Self-Advocacy is a Life-Long Process

For children and adults with learning disabilities and/or ADHD, self-advocacy is a life-long process. Receiving a diagnosis is only the beginning of the journey. Self-advocacy is how you use the diagnosis throughout your life to access supports, accommodations and resources so that you can experience success and a good quality of life. For parents, this may mean frequent communication with their child’s teachers to ensure that classroom strategies and supports are put in place. For adults, this may mean asking for access to a particular technology that will allow you to complete your work duties more accurately and efficiently. As you grow and learn more about how a diagnosis impacts you, your ability to self-advocate will strengthen and contribute to more positive outcomes in your life.

About the author: Krista Forand, M.Ed., Registered Psychologist, of Compass Psychology, practices in Calgary and is a member of the Network’s Supports for Adults Action Team. “Krista’s training and experience have primarily focused on working with youth and adults who, due to challenges with learning, attention, and social skills, have had difficulty achieving their potential. As a psychologist, she provides thoughtful and comprehensive psychoeducational assessments including learning assessments. This helps clients understand how they learn, process information and how they can help themselves achieve their goals.”

Did you have accommodations in high school?

Extra time on tests, a quiet testing space, extensions on assignments, or the use of assistive technology like speech-to-text software or a screen reader, are typical accommodations in high school classrooms. You may have had teachers who were understanding and supportive of your challenges with disabilities, whether physical or invisible like ADHD, Learning Disabilities or anxiety, and accommodated to varying degrees. However, it’s likely that the entire process of asking for and receiving those accommodations, which culminate in a formal, signed Individual Program Plan (IPP, IEP or LSP depending on your school board), was accomplished solely by your parents and teachers through rounds of calls, emails and meetings, with little input from you.

That is not how it works in post-secondary.

Accessing academic accommodations and support at the post-secondary level is significantly different to the way in which you received academic accommodations and support in high school. One of the key differences is that in the post-secondary landscape, the student plays a key role as a self-advocate. The student, not the parent, has the responsibility to initiate and be involved in the academic accommodation process. Many high school students with disabilities can feel especially overwhelmed by both the transition to post-secondary itself, as well as to their new role as a self-advocate. This sudden transition from being just a recipient of accommodations to now orchestrating them, can be both challenging and stressful.

What is the Duty to Accommodate?

In the post-secondary environment, increased independence and privileges are balanced by increased personal and academic responsibilities. The provincial legislation that establishes the Duty to Accommodate on the post-secondary institution includes a whole array of rights and responsibilities held by all the key stakeholders, including the students themselves. In some ways, accessing accommodations and supports at the post-secondary level is easier, and the range of ways to reduce learning barriers, more comprehensive and consistent than in high school simply because the legislation governing the processes is different. But it all begins with you, the student, being confident enough to start that ball rolling.

What do I need to say?

Consider how comfortable you are with the following skills:

- contacting the accessibility office either by phone, email or in-person

- meeting with an accessibility advisor

- discussing the impact of your disability

- describing which accommodations best support your learning

- approaching an instructor or professor to discuss your accommodations

- explaining accommodations to group members on collaborative projects

- advocating for yourself when difficulties arise

These communication skills are critical to your success as a student with a disability. If you did not have the opportunity to develop or hone these in high school or in some other setting prior to transitioning to post-secondary, then you need to practice them. Work with your parents or friends to role-play through various scenarios. Perhaps the guidance counsellor, learning support staff or one of your teachers at high school will set aside some time to work with you. Reach out to academic or self-advocacy coaches for practice sessions.

Become comfortable with talking about what you need to be a successful student. You have the right to accommodations, you have the responsibility to ensure them.

About the Author: Dr. Ana Pardo is passionate about empowering high school students with disabilities to advocate for themselves at the post-secondary level. She is the head of Academic Accommodation Advising – Bridge the Gap and has spent the last thirty-five years of her career examining disability, diversity and equity issues. Most recently, she has been the Director of Access and Inclusion Services at Mount Royal University and was previously the Director of Accessibility Services at the University of Calgary.

We know that even as adults, self-advocacy can be really tough. Whether we are explaining to our school principal that we need more supplies, the house painter that the job needs to be done this month, not next, or our physician that a medication is not working for us, we are advocating for ourselves. It can be hard getting others to listen, but we also know that it is necessary and provides a sense of power over our daily lives.

In our classrooms, self-advocacy for students goes hand-in-hand with metacognition, the personal awareness of how we learn. First, this requires an acknowledgement on the part of the teacher of the diversity of learning, recognizing that we all learn differently. Second is the understanding that self-advocacy is a life skill which is important to teach; the bonus being that it makes classroom management easier.

Modelling self-advocacy in the early grades

As always, good teaching begins with modelling. In the early grades, we instruct our students about classroom routines such as coming to the story circle or settling in after recess. Model for your students what works best for you.

“I’m most ready for reading circle when the papers are off my desk so I can see where our reading book is.”

Have them each tell what works best for them for coming to the reading circle. They will have a lot of different ideas:

“When my shoelaces are tied.”

“When I’ve checked the visual agenda.”

“When my learning buddy gives me the signal.”

Once your students have established what works best for each of them, you can just provide statements that remind them. “I am clearing the papers off my desk to get ready for story time. Is everybody doing what they need to do to get ready? Great! Now we’re ready to move to our circle.” This takes the pressure off you and puts the power and responsibility where it belongs, in your students’ hands.

When they reach upper elementary

In upper elementary grades, as students begin moving from class to class, teachers can model the same technique. At the beginning of each term, set the tone of accepting diversity in learning. Then model self-advocacy in your classes. You can begin saying something like:

“It works best for me if you all know what we are going to do in class, so I’ll put a mini-schedule for each period on the board. That will give you a minute to decide what you need to do so you’re ready to learn.”

That can be followed by a class discussion of the different ways students can demonstrate that they are ready to learn. It might seem like this takes too much extra time, but you’ll make that time back, because when students feel you are allowing them some control over their learning, you’ll spend much less time in organizing them and in managing the behaviour that results when students don’t feel they have power over their own learning.

When self-advocacy is modelled this way by teachers and expected of all students in a class, it becomes the norm for everyone. It creates the expectation that everyone has not only responsibility for their learning but has power over their own learning. It creates a culture of acceptance that means that students with special needs feel that they, too, have power over their learning.

Stepping up self-advocacy in high school

In junior and senior high, many students come to us with specific needs that must be individually accommodated. In my experience, most teenagers are not very skilled in self-advocacy. Most, but not all. I had a first-hand lesson in self-advocacy one day as a tiny blond tornado whirled into my office. Her jacket was half off, one shoelace was undone and her backpack was exploding papers, pencils and lunch bags in her wake. As she arrived, she waved some papers at me and said, “I have an IPP and my mom said you would help me.” Her statement was so unique that it opened my eyes to the fact that the other teens I worked with were not advocating for themselves.

With that insight, I realized that I’d been advocating for my students instead of giving them the power to do it themselves. So, I changed my practice. When students needed extra time, a quiet place to write, or to complete only some instead of all the math problems, we would rehearse together the conversation that needed to happen. First, my students needed to understand that the format of the conversation needed to be respectful, but also that expectations needed to be clear. They needed to understand, themselves, that they were not asking for a favour, they were explaining the need for appropriate accommodations so they could engage in learning. We made sure the conversation always started with some version of, “I learn best when…” or “I can show what I know if I can…” Once the conversation was ready, we would make an appointment with the teacher. I always went with the student for the first meeting and always offered to go to the next one. Surprisingly, that was never necessary! It seemed that once my students knew they could advocate for themselves, they were more than happy to do it independently.

Independence with self-advocacy is enhanced when teachers set the tone early in the semester or school year. Acknowledging to the whole class that everyone learns differently and that some people may need accommodations for their learning will open the door for students to approach teachers to explain what they need. One university instructor I know does it in his introductory lecture. Then he invites anyone who requires learning or testing accommodations to meet privately with him to plan what will work best for the student’s learning. He also reminds students that it is very hard to provide accommodations if he doesn’t know about them until twenty minutes before the final exam. He gets a great response from students who need accommodations – and he doesn’t run around in the minutes before exams anymore trying to match accommodations to student needs. It’s a method that works at the university level and it works just as well at junior and senior high school levels.

Self-advocacy is for every learner

Teaching self-advocacy starts with the acknowledgement of learning diversity. Everyone learns differently, not just those with special needs. Teachers who model self-advocacy demonstrate that it is important for all of us, that we all require different things to meet our needs sometimes and it is acceptable to ask for and expect to receive these. It paves the way for responsibility and accountability in the learning process. When we create a learning culture where self-advocacy is the norm and when we model that accommodations are necessities, not favours, we enable all our students to seize the power for their own learning.

About The Learning Disability

& ADHD Network

The Learning Disabilities and ADHD Network is a collaborative of a broad group of organizations and individuals in Calgary, which is operated through Foothills Academy Society.

Members of this long-standing Network regularly present at conferences, provide workshops and courses, undertake research projects in the field, collaborate with each other on various initiatives, and jointly create content for the website. Most importantly,

we are people whose lives have been touched by Learning Disabilities & ADHD, and whose life’s work it has been to support individuals with learning and attention challenges.

Disclaimer: The Learning Disabilities & ADHD Network does not support, endorse or recommend any specific method, treatment, product, remedial centre, program, or service provider for people with Learning Disabilities or ADHD. It does, however, endeavour to provide impartial and, to the best of our knowledge, factual information for persons with Learning Disabilities and/or ADHD.