About Learning Disabilities (LDs)

If you or someone you know is struggling with learning challenges you may be wondering if it is a Learning Disability (and what LD means?). In this section, we give you a description and definitions of Learning Disabilities, explain the process of getting an assessment, and help you to understand the diagnosis.

The difficulties were unexpected because these children were developing normally and did not have any of the conditions that might typically explain their difficulties in learning to read and write – they could see, hear, communicate, reason and problem solve, but they still struggled to develop literacy skills.

Official Definitions of Learning Disabilities

What is LD? Psychologists may use different definitions and criteria to diagnose a Learning Disability/Specific Learning Disorder. Two formal definitions are in current use by psychologists in Canada:

LDAC – Learning Disabilities Association of Canada – Official Definition of Learning Disabilities

Learning Disabilities refer to a number of disorders which may affect the acquisition, organization, retention, understanding or use of verbal or nonverbal information. This means an LD might affect how you learn, organize, remember or understand information.

These disorders affect learning in individuals who otherwise demonstrate at least average or higher abilities essential for thinking and/or reasoning. As such, Learning Disabilities are distinct from global intellectual deficiency, that is that they are not related to intelligence.

Learning Disabilities result from impairments in one or more processes related to perceiving, thinking, remembering or learning. These include, but are not limited to:

- Language Processing – understanding and expression of oral and written language; includes vocabulary, word structure, sentence structure and meaning across sentences.

- Phonological Processing – is the ability to identify the different sounds that make words and to associate and manipulate these sounds within words we speak and write.

- Visual Processing – is the ability to make sense of information taken in through the eyes. Difficulties with visual processing affect how visual information is interpreted, or processed by the brain.

- Processing Speed – refers to the pace at which you are able to perceive information (visual or auditory), make sense of that information, and then respond.

- Memory & Attention: Short-term memory is the process by which you hold on to information as long as you are concentrating on it. Long-term memory refers to the process by which you store information that you have repeated often enough. Attention is the ability to sustain attention to a tasks.

- Executive Function: Executive Functioning is needed for planning, organization, strategizing, attention to details and managing time and space.

Features of Learning Disabilities:

Learning Disabilities range in severity and may interfere with the acquisition and use of one or more of the following:

- Oral language (e.g. listening, speaking, understanding)

- Reading (e.g. decoding, phonetic knowledge, word recognition, comprehension)

- Written language (e.g. spelling and written expression)

- Mathematics (e.g. computation, problem solving)

Learning Disabilities may also involve difficulties with:

- Organizational skills

- Social perception & interaction

- Perspective taking

Learning Disabilities:

- Are life long.

- Change how they are expressed over an individual’s lifetime depending on the demands of the environment and the individual’s strengths and needs.

- Often lead to unexpected academic under-achievement or achievement which is maintained only by unusually high levels of effort and support.

- Are due to genetic and/or neurobiological factors or injury that alters brain functioning.

- Can co-exist with other conditions as ADHD, behavioural or emotional disorders, sensory impairments or other medical conditions.

For success, individuals with Learning Disabilities require:

- Early identification

- Specialized assessments

- Timely interventions and accommodations in the home, school, community and workplace

The interventions need to be appropriate for each individual’s learning disability and, at a minimum, include the provision of: specific skill instruction, accommodations, compensatory strategies, and self-advocacy skills.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition (DSM-5)

The DSM-5 was developed by the American Psychiatric Association.DSM-5 uses the umbrella term, ‘Specific Learning Disorders (SLD)’ and then areas of impairment and specific difficulties:

SLD with Impairment in Reading:- Word reading accuracy

- Reading rate/fluency

- Reading comprehension

- Includes Dyslexia

SLD with Impairment in Writing:

- Spelling accuracy

- Grammar and punctuation accuracy

- Clarity or organization of written expression

- Includes Dysgraphia

- Number sense

- Memorization of arithmetic facts

- Accurate or fluent calculation

- Accurate math reasoning

- Includes Dyscalculia

According to DSM-5, the diagnosis of a Specific Learning Disorder (SLD) includes the following symptoms:

- Persistent difficulties in reading, writing, arithmetic, or mathematical reasoning skills during formal years of schooling. Symptoms may include inaccurate or slow and effortful reading, poor written expression that lacks clarity, difficulties remembering number facts, or inaccurate mathematical reasoning.

- Current academic skills must be well below the average range of scores in culturally and linguistically appropriate tests of reading, writing, or mathematics. Accordingly, a person who is dyslexic must read with great effort and not in the same manner as those who are typical readers.

- Learning difficulties begin during the school-age years.

- The individual’s difficulties must not be better explained by developmental, neurological, sensory (vision or hearing), or motor disorders and must significantly interfere with academic achievement, occupational performance, or activities of daily living (APA, 2013).

One of the biggest challenges to tackle when you or your child have been diagnosed with a Learning Disability (referred to as Specific Learning Disorder with the DSM-5 Assessment) is to understand the terms that people in the education and psychology fields use to describe different Learning Disabilities and the terms for supporting or treating the LD.

We have grouped many of the terms here according to patterns of learning difficulties.

Accurate Word Reading, also known as Word Recognition or Decoding. If you are weak in this area it means that you struggle to associate the letters (graphemes) within a word with their sounds (phonemes) and to blend those sounds together to pronouce and read the word accurately.

Fluency means you can read at a good pace and with expression. People who struggle with accurate word reading also have a hard time reading fluently, particularly if the material you are reading is quite hard for you to read accurately.

If you have to work hard to read the words accurately and at a steady pace, then that might distract you from being able to focus on comprehending (understanding) what you are reading. That is why assistive technology, like ‘text to speech’ is a really helpful tool for people who struggle with word reading (decoding).

Learning Disabilities Association of Canada (LDAC) may identify the above challenges together as an impairment in phonological processing.

Phonological Processing is the ability to identify the different sounds that make words and to associate and manipulate these sounds within words we speak and write (sound blending, segmenting, playing with sounds, rhyming).

Phonemic Awareness Skills:

- Blend the individual sounds into a word (reading/decoding).

- Segment – break a word into syllables or individual sounds (spelling/encoding).

- Manipulate or change the sounds within a word. Example: Change ‘cat’ to ‘sat’.

Phonological processing, including the more specific phonemic awareness skills, is a foundational skill needed for learning to read words accurately.

The DSM-5 Assessment tool describes this type of Learning Disability as: Specific Learning Disorder (SLD) in Reading; word reading accuracy, reading rate/fluency.

Dyslexia: Dyslexia is a well-known term used to describe a reading disorder characterized by deficits in accurate and fluent word recognition. Spelling accuracy is impaired as well. The term dyslexia is not commonly used by psychologists as an official diagnosis when assessing for an LD. However, dyslexia is a term widely known, particularly by organizations, educators, and parents (i.e.organizations like the International Dyslexia Association and Decoding Dyslexia Alberta).

If comprehending (understanding) what you read or hear is what you struggle with, it may be because you have weaker language processing skills.

Language Processing: LDAC defines Language Processing skills as the understanding and expression of oral and written language; includes vocabulary, word structure, sentence structure, and meaning across sentences.

Language Learning Disability: LDAC defines a language learning disability as a disorder that may affect the comprehension and use of spoken or written language as well as nonverbal language, such as eye contact and tone of speech, in both adults and children.

Vocabulary can be described as oral vocabulary or reading vocabulary. Oral vocabulary refers to words that we use in speaking or recognize in listening. Vocabulary also is very important to reading comprehension. Readers cannot understand what they are reading without knowing what most of the words mean.

Specific Learning Disorder (SLD) in Reading – Comprehension (DSM-5). DSM-5 does not focus on the underlying processing skills that may be causing you problems, but instead the criteria is if you struggle academically with reading, in the area of Comprehension.

Spelling is also hard for someone who struggles with reading words accurately because you have to do the reverse process: 1) orally break the word into its individual sounds (segment), 2) identify and remember which letters represent those sounds, 3) and then say or write them down in correct order.

Dyslexia: People who are identified as being ‘dyslexic’ will struggle with spelling, along with accurate word reading and fluency.

LDAC definition: Processing impairments related to spelling and writing:

Spelling requires the ability to encode the sounds of a word into their appropriate print symbols. “When students are given strong spelling instruction focused on the orthography of English and learn to spell well, it positively impacts their ability to read (Ehri, 2000)

Orthographic Mapping is the encoding process in the brain that maps sounds to letters, turning unfamiliar printed words into instantly recognizable sight words.

Writing – Language Processing is the understanding and expression of oral and written language; includes vocabulary, word structure, sentence structure and meaning across sentences.

DSM-5 definition. SLD with impairment in writing (spelling, grammar, punctuation, clarity or organization of written expression)

- Number sense.

- Memorization of arithmetic facts.

- Accurate or fluent calculation.

- Accurate math reasoning.

The Learning Disabilities Association of Canada (LDAC) has identified specific processing challenges: Learning Disabilities result from impairments in one or more processes related to perceiving, thinking, remembering or learning.

These include, but are not limited to:

Language Processing: is the understanding and expression of oral and written language; includes vocabulary, word structure, sentence structure, and meaning across sentences.

Phonological Processing: is the ability to identify the different sounds that make words and to associate and manipulate these sounds within words we speak and write.

Visual Processing: is the ability to make sense of information taken in through the eyes. Difficulties with visual processing affect how visual information is interpreted, or processed by the brain.

Processing Speed: refers to the pace at which you are able to perceive information (visual or auditory), make sense of that information, and then respond.

Memory and Attention: Short-term memory is the process by which you hold on to information as long as you are concentrating on it.

- Long-term memory refers to the process by which you store information that you have repeated often enough.

- Attention: is the ability to sustain attention to a task

Executive Function is needed for planning, organization, strategizing, attention to details and managing time and space.

Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) is a lifelong condition that makes it hard to learn motor skills and coordination. It’s not a learning disorder, but it can impact learning. Kids with DCD struggle with physical tasks and activities they need to do both in and out of school.

Dysgraphia is having difficulty with the physical act of writing.

More recently, DCD has become the more recognized term used to describe challenges with motor skills and coordination, such as difficulty with the physical act of writing. Occupational Therapists (OTs) may work with a person struggling with dysgraphia or DCD to improve motor skills.

Nonverbal Learning Disability (NVLD) describes a well-defined profile that includes strengths in verbal abilities contrasted with deficits in visual-spatial abilities. Individuals with NVLD often have trouble with some of the following: organization, attention, executive functioning, nonverbal communication, and motor skills.

- Lifelong: Individuals do not grow out of Learning Disabilities, although the impact may change with changing life demands.

- Heterogeneous: Learning Disabilities are heterogeneous. There are many patterns of strengths and needs and levels of severity. Not all individuals with LD have the same strengths and difficulties. Different terms have been used to describe some of the different patterns of difficulties: dyslexia, dysgraphia, etc.

- Differences in processing information: Individuals with LD can learn, but they learn differently because they process information differently. Their brains are wired differently so they deal with information in different ways. The differences may be in how they take in information through the senses, in how they make sense of the information and give it meaning and/or in how they express what they know through speaking, writing, demonstrating, etc.

- Associated with academic under-achievement: For individuals with LD, the most obvious negative impact in their lives is on the development of academic skills, most often reading and writing.

- Neurologically (brain) based: Brain research has shown that LD results from a difference in the way an individual’s brain is “wired”. Structural brain differences have been found. Most importantly, brain imaging studies have demonstrated that during reading, the activation patterns of brains of individuals with LD differ from those of typical readers’ brains.

- Often hereditary in families: When the LD affects reading, between 25% and 50% of children with LD have a parent who has LD.

- Not “walking alone”: Individuals with LD often have other difficulties. For example, 30% to 50% also have Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Anxiety and depression are also common.

- Not an intellectual disability: Individuals with LD have at least average intelligence. They do many things well and have an uneven profile of abilities and difficulties. This is in contrast to an overall intellectual disability that affects all aspects of learning and development in a person.

- Not a result of poor educational history: Individuals with LD have had opportunities to learn; poor teaching does not cause LD though it may complicate it.

- Not a result of socio-economic factors: LDs occur across all socio-economic levels, although access to opportunities and supports may vary across income levels.

- Not a result of cultural or linguistic differences: LD can occur in any cultural or economic group. Cross cultural research indicates that individuals exhibit characteristics associated with LD across the world.

- Not a result of emotional disorders: Many individuals with LD experience anxiety and depression as a result of their learning difficulties, but the emotional disorders did not cause the learning difficulties.

- Not a result of vision or hearing problems: It is important to ensure that individuals do not have uncorrected hearing or vision problems as those can make reading more difficult, but it cannot cause a learning disability.

References/Resources

LD Association of America (LDAA)

Book: Multisensory Teaching of Basic Language Skills. By Judith Birsh & Suzanne Carreker

Learning Disabilities (LD) are common and affect approximately 5 – 15% of people around the world. They are considered an “invisible disability”.

Learning Disabilities have biological origins even though the exact causes are not truly understood. A combination of genetic (e.g. hereditary brain wiring) or environmental (e.g., injury before or during birth, low birth weight) factors cause differences in the brain. This affects how the individual perceives or processes different types of information.

We can actually see physical differences between the brains of those with LD and those who do not through neuro-imaging. Depending on the LD, we can see differences in size and level of activity in certain areas of the brain when compared to the brain of the same age without a LD. Simply put, their brains are wired differently.

While the exact causes of Learning Disabilities are unknown, we do know that they are NOT caused by:

- Ineffective teaching.

- Poor parental support.

- Economic disadvantages.

- Health-related problems.

- Lack of exposure to schooling/instruction.

- Sensory deficits.

These factors, though, can contribute to a student’s learning progress and later academic success.

There is a saying that can apply to the LD population: “If you have met one person with a Learning Disability, you have met one person with a Learning Disability.” This saying highlights the fact that LD can show up differently in each individual.

A key feature of those with an LD is the unusually high level of effort and support required for the individual to achieve at the same level as their peers despite their strong potential.

Without identification and proper support, individuals with an LD are at an increased risk for negative outcomes in many areas of life.

Social and Emotional Difficulties: Individuals with LD are significantly more likely than their non-LD peers to struggle with social and emotional difficulties for many reasons. For example, individuals with LD can have significant frustration and struggles with academics affecting their self-esteem.; they are also more likely to be teased or bullied in school settings due to their academic struggles.

Less Education: Data shows that individuals with learning and attention issues are significantly less likely than those without LD/ADHD to complete post-secondary education. When not supported, individuals with LD can experience significant difficulties with academics that discourage them form pursuing further education.

Lower Employment: In the workforce, individuals with LD/ADHD have higher rates of unemployment, underemployment and lower incomes compared to other young adults.

Higher Mental Health Issues: The data also shows that they report mental health issues at more than twice the rate of young people without LD. Additionally, these individuals are at a greater risk of engaging in risky behaviours (e.g., alcohol/drug use) and suicide.

It is important to remember that we are talking about an increased chance of problems. These problems are not inevitable. Proper diagnosis and treatment of of an LD are important ways to decrease the risks individuals will face. Furthermore, providing people with opportunities to find “islands of competence” (i.e. sources of pride and accomplishment) can help to build their self-worth and resiliency.

UNDERSTAND LEARNING DISABILITIES: Developing a greater understanding about Learning Disabilities is an important way to reduce stress for the person living with an LD, and also for other people in their lives, including employers.

Benefits include:

- The individual gains an understanding of their learning profile, strategies to manage their specific LDs, and also have a greater awareness of their strengths.

- A person is more likely to advocate or ask for help for themselves if they understand how the disorder affects them.

- A person is less likely to feel bad about themselves if the people around them understand their struggles and the best ways to support them.

- When family members, teachers, and peers/colleagues learn about LDs, they are less likely to be frustrated with the individual.

- They are more likely to have appropriate expectations and use helpful strategies.

- Everyone can adopt a strength-based approach; appreciate and highlight all of the positive skills and aptitudes the person has, while recognizing the extra effort the individual must put into managing their LD.

There is no way to “cure” Learning Disabilities but research supports the two most common treatments: remediation and accommodation.

REMEDIAL INSTRUCTION:

(Special teaching techniques) Remedial instruction targets the particular skill in which the individual is showing gaps. For children, remedial instruction may be provided as part of a student’s school programming (e.g., pull-out instruction in small groups) or arranged outside of school by families privately.

Adults can also access remedial instruction in the community and in some cases through post-secondary institutions.

ACCOMMODATIONS:

Accommodations help to level the playing field for individuals with Learning Disabilities and ADHD.

Children: For students in the school setting, accommodations do not change the curriculum the child is expected to learn. Instead, they provide what the child needs in order to access the curriculum (i.e., changes how they learn). In other words, they lower the barriers in the classroom, not the bar!

Examples of accommodations include:

- Instructional/environmental

- Testing

- Assistive technologies

Adults: Adults with a diagnosed disability, including an LD or ADHD, have a right to accommodations in both the post-secondary and workplace settings.

ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGIES:

In our 21st century world, technology is important for everybody, but it particularly represents a key strategy in supporting individuals with LDs.

Assistive Technology involves any device, equipment, or system that allows an individual with a disability to work around their challenges. It can vary from very simple technology (e.g., calculator) to more complex (e.g., text-to- speech software).

Many assistive technology tools can be used throughout the student’s education, including at the post-secondary level, and in the workplace.

The type of remedial instruction and accommodations needed by an individual will depend on their learning profile and specific LDs. These may change as the individual develops effective strategies or is faced with different demands.

Learning Disabilities – What Parents Need to Know: Foothills Academy Parent Handout

Psycho-eductional Assessment:

Below are common questions and answers regarding how to get a psycho-educational assessment and what to expect during an assessment for Learning Disabilities.

You or your child may benefit from an assessment if there are struggles with:

- Reading, writing, math, or language skills

- Understanding and remembering things

- Paying attention so you can be present for learning

- Getting along with peers, teachers, and family members

- Worrying, nervousness, and/or irritable mood

A psycho-educational assessment looks at how a person learns and what kinds of things may be getting in the way of their learning. The information that is gathered through a psycho-educational assessment helps make decisions about how to help the individual.

Registered psychologists who have specific training in psycho-educational assessments can provide these types of assessments. Training refers to the type of schooling they received, as well as practical experience they have had working with clients under supervision by another psychologist.

Schools: Parents should always check with their child’s school first to see if the school psychologist can conduct a psycho-educational assessment. There is no cost for this service, but schools often have long waiting lists, and your child is not guaranteed to be assessed.

The health care system: In some cases, there may be a special program or clinic within the health care system that can offer psycho-educational assessments, however, the eligibility criteria are often very specific and require a referral from a physician. It is worth enquiring about this option, as it would be covered by Alberta Health Services (AHS).

Non-profit organizations/agencies: Registered psychologists will often work within non-profit agencies and are qualified to provide psycho–educational assessments. There is often a cost but many run on a sliding scale. Alternatively, funding assistance may be available.

Private practice psychologists: In Alberta, there are many psychologists who work in private practice who are also qualified to provide psycho–educational assessments. You will have to pay out of pocket for this option. However, some insurance plans may cover some of these services. You can search for psychologists through the Psychologists Association of Alberta.

Here are some questions that you can ask a psychologist to determine if you feel comfortable working with them.

What kind of training have you had in psycho-educational assessments?

Ideally, the psychologist will have attended graduate school in either a clinical psychology or school psychology program that specifically focused on psycho-educational assessments, Learning Disabilities, and related challenges. They should also have had practical experience using their skills with clients under the supervision of another psychologist who has this training.

Sometimes psychologists trained in other areas of psychology, such as counselling, will learn how to do assessments outside of a structured graduate school program. In these cases it will be important to discuss what kind of training they participated in and whether they were supervised. Attending a workshop about using a particular intelligence test is not sufficient training to be conducting psycho-educational assessments.

What types of information do you gather for the assessment?

A psychologist who is qualified to conduct psycho-educational assessments should be gathering multiple types of information (e.g., interview, questionnaire, standardized testing) from multiple sources (e.g., the child, the parents and the teacher). Ask them how they make decisions and draw their conclusions. Diagnoses should never be made based on one test or questionnaire.

What is a Learning Disability? How is it diagnosed?

A qualified psychologist will be able to answer these questions, as they would have studied Learning Disabilities and learned how to diagnose them during their training.

To understand what a Learning Disability is go to LDs – Definitions & Terminology

Be open. You may have an idea of what the problem is or perhaps you may even think that you or your child has a particular disorder or meets criteria for a specific diagnosis. It is fine to have hunches about these things, but keep in mind that the end results of the assessment may point to something different. A good psychologist should have an open mind as well.

Be planful. Engage in the assessment process at a time that is not too busy or stressful for you or your child. The psychologist will want to get the best “snap-shot” of what you or your child is capable of and what you/they are typically like in everyday life. For example, it would not be best to start the assessment process after a death in the family, as you/your child may be behaving differently as a result of grieving.

Be prepared. Gather ahead of time all of the relevant information (ie., report cards and any previous assessment reports or other medical or educational documentation). This will save time and make the process go more smoothly. It will also help the psychologist in forming conclusions, as it gives them a better sense of the bigger picture.

Be careful and thoughtful. Not every problem requires a psychoeducational assessment as the first solution to a problem. Counselling, academic support such as tutoring, or other strategies may be tried first. Ask the psychologist what are some of the other options and the pros and cons of waiting.

Be realistic. It is helpful to understand that a psycho-educational assessment will provide you with information about how you or your child learns, but it will not provide solutions to every problem or quick fixes. Many of the recommendations involve hard work and dedication to a new way of learning and working. Start with recommendations that are manageable and meaningful and move forward from there. Be patient.

Be active and interested. When the assessment is complete and you meet with the psychologist to get the results, actively listen, take notes, and ask any and all questions that you might have. You want to leave that appointment feeling confident about your next steps. If you don’t understand something, ask the psychologist to explain it further.

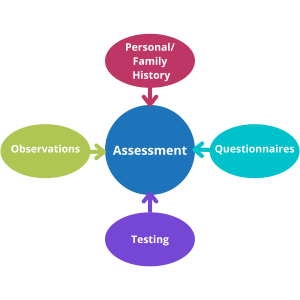

A psycho-educational assessment is conducted by a registered psychologist who has training in this particular type of assessment. The types of information gathered include:

Personal background information through interviews with parents, teachers and/or the individual. Examples of information gathered include birth and developmental history, education history, medical and health information, and family relationships.

Questionnaires that may look at the person’s behaviour, daily living skills, attention, mood, and social skills.

School records, which include report cards, teachers’ letters, and other assessments.

Sometimes observing the child in their classroom setting can be helpful for understanding their behavior and learning challenges.

Standardized testing, which looks at things like a person’s intelligence, academic skills, memory, and language abilities. These are typically standardized, norm-referenced tests. Standardized means that when they created the test, they made very specific instructions that everyone giving the test must follow, and they gave it to lots of people who are a representative sample of the population. Norm-referenced means that they have statistical information that allows the psychology to compare your child’s performance with other students her age and/or grade.

Standard Scores: These are typically scores that give a number based on several smaller tasks. On these tests 100 is the middle score. Percentile Ranks are easier to understand though.

Percentile Rank: This score tells you how well you or your child performed compared with a person the same age or grade. These are numbers that range from less than one to just under 100, representing the performance of 100 people who are the same age. If your score is at the 10th percentile, that means that you performed better than or equal 10 out of 100 other people the same age. If your child’s score is at the 75th percentile, that means that he performed better than or equal to 75 out of 100 children his age.

Referral Questions: What types of tests, questionnaires and observations will be done will depend on what you and the psychologist decide will be the primary focus of the assessment. This is often called the “referral question”. Referral questions help to give the assessment a purpose.

Common referral questions include:

- Why am I or my child struggling to learn to read?

- Why am I or my child struggling in all academic areas?

- My teenager works very hard, but doesn’t seem to be getting grades that reflect this effort. Why?

- Do I or my child have a Learning Disability?

- What can help with my or my child’s learning?

Personal/Family

History

Observations

Assessment

Questionnaires

Testing

After the psychologist has gathered all the information that they need to answer the referral question, they can start to make conclusions about the individual’s learning.

It is important to understand that conclusions are not made simply on the basis of tests scores. Conclusions are based on the combination of test scores, background information, education history, observations and other relevant information. This is why a psycho-educational assessment is not a quick process and involves making sure that all relevant information is available for the psychologist to consider before they draw their conclusions.

Post-Assessment Meeting: Once all information is gathered the psychologist will meet with you to discuss the results of the assessment, any diagnoses that were made, and what may help. This information should be explained in a way that makes sense to you. If something doesn’t make sense, ask about it. It’s your right as a parent to understand the results of your child’s assessment. It’s also your right to understand your own assessment.

If a diagnosis is made, the psychologist will discuss with you the importance of sharing the assessment results. You should receive a report that you can share with others. However, the ultimate decision on whether or not you share the assessment is up to you.

You should have a meeting where the psychologist explains the results to you. During the meeting and after you receive the report, you should ask the psychologist for more information

Here are a few questions to ask yourself about the report:

- Did the report capture the question I was asking about myself or my child?

- Did the report answer the question I was asking about myself or my child?

- Did the report explain how the data was used to come to the conclusions and diagnoses?

- Did I understand my or my child’s functioning in each of the areas measured?

- Are there practical recommendations included?

- Are the recommendations connected to the individual’s strengths and weaknesses?

Educational psychologists in Canada may diagnose a Learning Disability with the LDAC definition and/or a Specific Learning Disorders, using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Whichever diagnostic assessment the psychologist uses, it should be explained clearly in the report and during your meeting.

Intellectual Disabilities could be identified instead of LD. Intellectual disabilities, as defined by the DSM-5, require three things:

- Significant challenges in reasoning, problem solving, abstract thinking, and planning, which is measured using an intelligence test. Intelligence test scores would be lower in a person with an Intellectual Disability as compared to someone with a learning disability.

- Significant challenges in daily living skills, which include things like communication skills, self-care, managing money, being independent in the community and at home.

- Evidence that the challenges in number 1 and 2 started when the person was a child.

For more information about Intellectual

For more information about Intellectual Disabilities visit AAIDD.ORG.

Giftedness:

Technically, giftedness isn’t a diagnosis because it isn’t considered a disability. However, some parents may want a psycho-educational assessment for their child if they wonder about giftedness. Giftedness can co-exist with LD.

Different school boards and organizations define giftedness in different ways. Within the context of a psycho-educational assessment, giftedness usually requires intelligence test scores that are in the top 2% of the population. Knowing whether a child is gifted can be helpful in determining what kinds of educational programming may be beneficial for them.

Other Diagnoses:

Other diagnoses that can be made through psycho-educational assessments include: ADHD, General Anxiety Disorder, and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). A diagnosis of ASD usually requires additional extensive interviewing with the parents and play-based testing with the child.

As ADHD is a condition that can be medically managed, it is often diagnosed by physicians (family physicians, pediatricians, psychiatrists). ADHD may also be diagnosed within the context of a psycho-educational assessment.

It is important to understand that technically a psycho-educational assessment is not necessary to diagnose ADHD, as the diagnostic criteria for ADHD are behavioral (e.g., loses things). A thorough interview with the family, questionnaires and observations are often used to diagnose ADHD.

However, it may be necessary to also do a psycho-educational assessment, particularly when there may be concerns about underlying learning difficulties. This would be important to fully understand all of the challenges that the child is facing including ADHD.

Keep in mind that there are no “tests” for assessing ADHD. There are tests out there that measure attention in different ways (e.g. being able to focus for long periods or being able to stop yourself from doing something). However, these are mostly used in research settings and are not considered appropriate for diagnosing ADHD.

If a professional wants to solely use a test to assess for ADHD and does not conduct a comprehensive interview to learn about possible ADHD symptoms in everyday life, consider working with someone else.

Disclaimer: The Learning Disabilities & ADHD Network does not support, endorse or recommend any specific method, treatment, product, remedial centre, program, or service provider for people with Learning Disabilities or ADHD. It does, however, endeavour to provide impartial and, to the best of our knowledge, factual information for persons with Learning Disabilities and/or ADHD.