Learning Disability

and ADHD Support

When You Need It.

Resources For

Greater Success

We hope that this website supports your journey as you navigate the struggles related to LD and ADHD and build upon your strengths, in order to reach your full potential. Know that you are not alone, and we are here to help you along the way.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Have a Question? Get in Touch Today!

Latest News

April 2025 Newsletter

Save The Date | Spring Programs | New Blog Articles | Educators & Employers

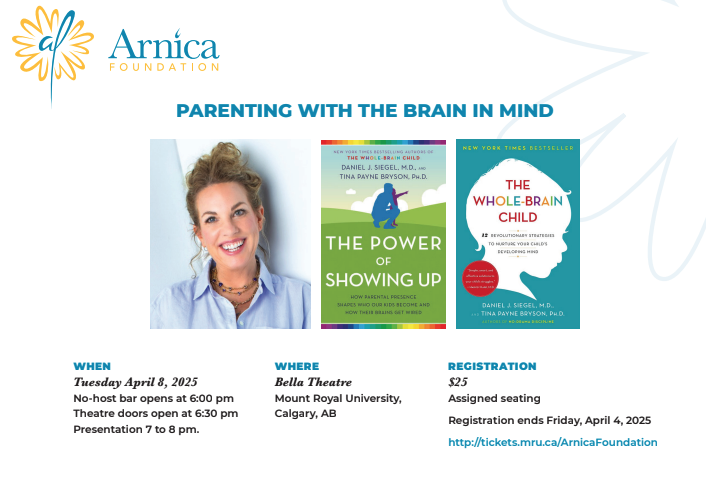

Parenting With The Brain In Mind

Join Dr. Tina Bryson for an inspiring look into a child’s brain and better parenting strategies.

March 2025 Newsletter

Latest News | Summer Camps | New Blog Article | And More!

Join us at an Upcoming Event

Featured Event

Find Your Path: Strategies for Success Conference

Date of Event: October 26th, 2024

October is Learning Disabilities and ADHD Awareness Month! Boost your understanding and personal support toolkit at our one-day conference on October 26, 2024.

Find Your Path: Strategies for Success is all about practical take-aways for those with Learning Disabilities or ADHD on executive functioning, mental health, ADHD medication, math strategies, advocacy, relationships and more!

If you are a parent, educate children or are an adult looking to strengthen your skill set, this conference is for you.

Lethbridge, Alberta Canada

EXPERT: Dr Peg Dawson This interactive 2-day workshop offers educators, school psychologists, special education teachers, and other professionals working with children and adolescents, a comprehensive understanding of executive skills and […]

Calgary, Alberta Canada

Join the Learning Disabilities Association of Alberta on May 10 for a full day of sessions by local experts. This conference is an in-person full day event that focuses on […]

Calgary, Alberta T2N4T1 Canada

Join us for a fun and interactive workshop where we’ll dive into simple ways to help boost your child or teen's social and emotional skills. We’ll talk about everything from […]

Recent Blog Posts

Learn more about LDs and ADHD, and find helpful information and insights on the assessment, diagnosis and management of these learning and attention challenges.

Burnout is a term used to describe being in a state of shutdown. Symptoms of burnout vary from person to person; however, they often include fatigue, emotional numbness, body pains, increased or decreased sleep, and apathy.

Burnout can be understood through the Spoon Theory, an analogy created by Christine Miserandino to explain variations in physical, emotional, and mental energy. Everyone has a set amount of spoons per day. Everything you do takes a spoon. Burnout occurs when you have no spoons left and you are trying to continue. The good news is that learning how to recover from burnout is possible. The same skills that help with recovery can also be used as preventive care practices.

How Do You Rethink Burnout?

For both recovery and prevention, the first step is rethinking mental wellbeing as separate from physical wellbeing. Instead of being separate, mental and physical wellbeing are intertwined. Therefore, it is important to explore both your feelings (physical bodily reactions) and your emotions (labeling or categorizing these feelings). As a neurodivergent individual, your experiences may have been invalidated in the past. Therefore, reflecting on your feelings and emotions as an adult may be a new experience.

Getting To Know Your Feelings

Understanding your feelings as physical reactions is tied to your perception of your body. Depending on your neurological wiring, you may be more, or less, aware of your own body. This awareness of your body is called interoception. Interoception includes awareness of the variety of internal sensations in the body, such as heart rates, hunger, temperature and pain. Interoceptive feelings include:

- I recognize that I’m hot before sweating or cold before shivering.

- I regularly can feel my heartbeat.

- I notice discomfort before I become stiff or sore.

A person with high interoception would be hypersensitive of their physical sensations and could be easily overstimulated by them. For example, wearing clothing with tags feels painful. In contrast, a person with low interoception would not be aware of physical sensations until they become more extreme such as not noticing thirst until becoming dehydrated or not using the bathroom until it is urgent.

How Are Emotions Different From Feelings?

Emotions are tied to labeling and thinking. Emotions involve interpretations and meaning making; therefore, emotions are a cognitive activity. Cognitive emotions are often constructed by past experiences as well as current values and beliefs. Cognitive emotion awareness includes:

- I can identify the emotion I am feeling at any given time.

- I differentiate between similar emotions, such as frustration and disappointment.

- I can explain why I have a particular emotion.

A person with high cognitive emotional awareness might have intense emotional states, and may have multiple, complex and conflicting emotions at the same time. They may spend a lot of time thinking about their emotions, which can be overwhelming.

A person with low cognitive emotional awareness might struggle to explain or label their emotional state. They may have difficulty understanding causes of their emotions or impacts emotions have on them. For example, someone believing that nothing ever seems to bother them.

Mapping how you experience Interoceptive Feelings (IF) and Cognitive Emotions (CE) allows you to better identify the circumstances that impact your wellbeing.

A neuroinclusive, embodied approach to wellbeing means learning how to recognize your individual signs of distress and learning the skills to recover. In other words, you need an approach that helps you to identify when you are running low on spoons.

Helpful Tips

Here are few helpful tips to start you on this journey:

If you have Low Interoceptive Feelings: Body sensations may not be felt until they are overwhelming. As a result, you may not get physical warning signs of running out of spoons. In particular, individuals in hyperfocus or flow state are particularly prone to this challenge. External reminders for breaks or check-in can be a helpful tool. You may also have to proactively check-in with your body to help maintain your wellness during your flow states.

If you have High Interoceptive Feelings: With constant bodily feedback, high interoception individuals are likely to experience overstimulation that can result in burnout. You may find that reducing sensory input can help protect your spoons. For example, reducing stimulus in your environment or adjusting lighting may help save spoons for more critical tasks. Moreover, you may experience burnout first as physical feedback. You will likely find embodied activities, such as mindfulness, helpful when dealing with stress.

If you have Low Cognitive Emotions: You may have difficulty thinking about or labeling your emotions. Consider looking for physical cues that are commonly associated with emotions. For example, rapid heartbeat is often experienced with anxiety. You may want to try non-cognitive or non-verbal approaches to exploring feelings. For example, you might find art, music, and other ways of expression better reflect your understanding.

If you have High Cognitive Emotions: Since you can easily label and verbalize emotion, you might find you get overwhelmed in thoughts or talking about feelings. There are a multitude of ideas and meanings going on at once. You may find using structures for organizing and categorizing help make sense of your experiences. An example of this is using bullet journals. Similarly, verbal or cognitive strategies like reframing may help support your wellness.

Rebuilding Your Wellness

By recognizing the interconnection of the body and mind, you can better understand how to support your own wellness. Engaging in sensory explorative behaviours as children may have been discouraged or even punished by family, community, or school educators. Because of this, many neurodivergent people were taught to ignore or dismiss these experiences as children, leading to internalized stigma or shame as adults.

As an adult, you can build renewed awareness of your experience of feelings and emotions. Understanding your body/mind connections means learning how to recognize and recover from distress that uses up your spoons. You can help prevent burnout, support your wellbeing, and reach your goals by practicing ways to save your spoons for what is important to you.

About the Authors: Brenda McDermott is the Senior Manager of Student Accessibility Services at the University of Calgary. She completed her PhD in Communication Studies in 2015. As a lifelong learner, she returned to school to complete a Masters of Education in 2021. She has a passion for improving the student experience, exploring Generative AI tools, and discussing Universal Design for Learning.

Jess Lopez (they/them), is proudly neurodivergent and epupillan (Mapuche 2Spirit). Jess runs the Neurodiversity Support Office at Student Accessibility Services, University of Calgary, and pursues MEd graduate studies in Educational Research. Jess provides innovative, neuro-affirming, embodied approaches to wellbeing for students and educational training for staff and faculty to help foster a neuroinclusive campus community that values different ways of knowing and being.

If you look up the title above, you will be directed to resources for individuals with ADHD to advocate for themselves, make themselves better understood or make it easier for others to work with them. There are little to no resources out there for employers or organizations to better communicate with neurodivergent folks in order to make their workplaces more accessible.

I’ve had several conversations with adults who were diagnosed late in life with ADHD, and the common thread in these conversations is a sense that we can do better to make our collective communication more digestible. Two of the adults I consulted, who were diagnosed with Severe ADHD in their forties, gave me some actionable tips for written and verbal communication with neurodivergent individuals.

The ideas they conveyed were very similar, and they align with what research I actually could find. Using some of these tips will help neurodivergent and others digest information more readily.

Written Communication

Written communication should be concise. Long, languid texts are hard to follow, and folks can lose interest or focus on the topic, often because their working memory is overtaxed. Some ways to make text more accessible are:

- Emails or messages can be about just one topic

- Spacing, bolding keywords and colour coding information is helpful

- Bullet points and lists make details easier to consume

- Send just one version of an email or communication so as not to confuse people

- Try not to send blanket messages that may not apply to everyone

- Avoid large blocks of text and opt for smaller chunks

- Be direct in what you are communicating; subtlety may be lost

- Step by step lists or instructions, using numbers and clear instructions will be easier to digest than paragraphs

Verbal Communication

Verbal communication often requires a great deal of nuance. To ensure you are being understood and to make it easier for folks with ADHD, you can add some of the following tips to your toolbox.

- Be patient – make space of potential interruptions and digression

- Be clear in your meaning and what you are requesting

- Make space for follow up questions and clarifications

- List tasks or requests in a sequential order

- Try to understand the person’s communication style and adapt as you can

- Follow up with written communication if making a request or relaying important information so it can be referred back to later

- If someone discloses that they have ADHD, take note so they don’t have to remind you

- Make eye contact and be mindful of your body language

- Be prepared to monitor digressions and prompt people to return to the topic

These are just some ways that people can make communication more readily digestible for folks with ADHD and even other types of neurodivergence. Remember that reducing barriers wherever possible is good for all types of people, and it will make your workplace or organization a better place to work and get things done.

About the Author: Dara MacKay is a Calgary educational professional who has worked extensively in the post-secondary education sector and has been in education for over 20 years in many capacities. Dara is passionate about serving populations who experience barriers, working to reduce them and connect students with strategies and resources that help lead to success. Dara is a member of the Learning Disabilities & ADHD Network’s Supports for Adults Team.

If you are a parent of a child who has been recently diagnosed with ADHD or a learning disability, you have likely asked yourself, “How should I tell my child?”

The first step in talking to your child about their diagnosis is to speak with the professional who provided the assessment and ask them how they would explain it. As a psychologist, I try to keep explanations of learning disabilities and ADHD age-appropriate and strengths-based, and allow families to ask questions.

“We’ve learned that your brain is built differently and that’s ok. It makes some things easier and others more difficult, and now that we know, we can work with that.”

For all ages, it will be important to help the child understand what their strengths and challenges are and how to ask for help when needed. Having a diagnosis is an explanation for why certain things may be easier or more difficult for your child compared to their peers. It will also be important to strike a balance between providing support and supervision to your child when it is required and giving them a manageable level of independence to improve self-esteem and confidence as they mature.

How Do I Explain A Diagnosis?

An important part of explaining a diagnosis to a child (or to anyone for that matter) is to distinguish between the challenges that arise from the diagnosis and the child’s character. For example, ADHD has been well established as a medical condition that involves differences in brain functioning, particularly in the frontal lobe and cerebellum, and with the neurotransmitter dopamine.

It is important to explain to your child that ADHD does not mean that they are lazy or stupid or that they don’t care about doing well in school (or at home or with their friends), but rather, it is an actual difference in how their brain operates, which makes it hard for them to direct their attention to the right task, at the right time, with the right amount of energy.

Using a Simple Example: Wearing Glasses

We understand this difference between condition and character when we talk about other diagnoses. For example, most of us would not tell a person who is nearsighted to simply try harder to improve their vision. There is an actual difference with how their eyes work compared to someone with 20/20 vision and no amount of trying harder to see better is going to improve that. Instead, we recognize the difference and we provide the person with glasses or contact lenses so that they can see just as well as someone who isn’t nearsighted. Similarly for ADHD and learning disabilities, we can explain to children that we know they are trying their best and now that we also know their diagnosis, we can support them with additional targeted instruction, accommodations, and other supports at home, school, and in the community.

How Do I Actually Word This?

How you explain a diagnosis to your child will depend on many factors, such as their age, social-emotional maturity, and how the diagnosis specifically impacts their daily life. For younger children, it will still be important to explain the diagnosis to them but in terms that they can understand and that don’t overwhelm them. For teenagers, parents may also want to focus on having important discussions about relationships, safety (e.g., driving), and self-advocacy.

Explaining Brains by Dr. Liz Angoff offers scripts and other tools that parents can use. This page is specifically about explaining a diagnosis to a child.

Getting Rid of “Try Harder”

When we separate the child’s character from their ADHD or learning disability then we remove the shame and sense of defeat that often comes as a result from frequently being told to “try harder.” When we describe the diagnosis in a clear and fact-based manner, we separate the child from the condition and allow them to accept it and not to over-identify with it. Your child is much more than their ADHD or learning disability but their diagnosis is also a part of their lived experience that needs to be recognized, accepted, and supported.

About the author: Krista Forand, M.Ed., Registered Psychologist, of Compass Psychology, practices in Calgary and is a member of the Learning Disabilities & ADHD Network’s Supports for Adults Action Team. “Krista’s training and experience have primarily focused on working with youth and adults who, due to challenges with learning, attention, and social skills, have had difficulty achieving their potential. As a psychologist, she provides thoughtful and comprehensive psychoeducational assessments including learning assessments. This helps clients understand how they learn, process information and how they can help themselves achieve their goals.”

About The Learning Disability

& ADHD Network

The Learning Disabilities and ADHD Network is a collaborative of a broad group of organizations and individuals in Calgary, which is operated through Foothills Academy Society.

Members of this long-standing Network regularly present at conferences, provide workshops and courses, undertake research projects in the field, collaborate with each other on various initiatives, and jointly create content for the website. Most importantly,

we are people whose lives have been touched by Learning Disabilities & ADHD, and whose life’s work it has been to support individuals with learning and attention challenges.

Disclaimer: The Learning Disabilities & ADHD Network does not support, endorse or recommend any specific method, treatment, product, remedial centre, program, or service provider for people with Learning Disabilities or ADHD. It does, however, endeavour to provide impartial and, to the best of our knowledge, factual information for persons with Learning Disabilities and/or ADHD.